To project the artwork onto a smartboard click here.

Piero di Cosimo is one of the most interesting artists of the Renaissance. His biographer was Giorgio Vasari, the contemporary of Michelangelo who is considered to be the first art historian. Vasari collected stories about the most famous and popular artists from the Renaissance, and his book, The Lives of the Artists, became a bestseller. His narratives are full of personal remarks, perhaps based on hearsay and his own judgment, on the character of both the art and artists themselves. With that as the basis, we come to know Piero di Cosimo as a true eccentric. He had unusual habits and phobias that often kept him in seclusion. According to Vasari, he was deathly afraid of thunderstorms and fire, lived on a diet of hard-boiled eggs, and never cleaned his studio. He also had a deep love of nature, which usually showed in his painting of trees, rocks, animals, and the natural world. Despite his apparent eccentricities (if Vasari’s narrative is true), Piero accomplished a remarkable body of work, including this beautiful scene of the Nativity.

The Nativity with the Infant St. John is a tondo painting—one that is circular in shape, which was popularized in the Renaissance. While the subjects varied, the tondo sometimes functioned as a gift to celebrate a successful birth, called a desco da parto or “birth tray.” During the postpartum period a mother would receive limited guests, usually only females and family, and gifts and refreshment would be served from such an image framed and functioning as a tray. But the practical function was ritualistic only at first; later, the object would be hung as a framed work of art. A repeating iconographic subject for such a desco da parto was the birth of a saint, or as in the case here, the Nativity of Our Lord.

It is important to consider that the circular image would offer the artist the opportunity (or challenge) to compose “in the round.” If we consider the rose window in the Gothic Period as an immensely successful expression of circular composing, the relative flatness of a window permits the designer to think largely in two dimensions. But when an artist must conceive of the wholeness of three dimensions, the challenge increases. In a rose window, the form is of a flower or a wheel—petals or spokes radiating outward from a center ovule or hub. But in a painting of a landscape with human figures, how can an artist make a convincing picture and still get the sense that the circle’s form is important to the image and the image is important to the circle?

Circles are “perfect”; circles have no beginning or end—they are continuous with no parts or characteristics that offer differences, such as the corners found in squares or triangles, two other basic geometric forms. In that sense, circles are inscrutable. This is a good reason to symbolically associate circles with perfection and unity. One might also extend that comparison to God, who is a unity of pure being even in the perfect familial unity of the Trinity—a beautiful and mysterious paradox. In visual art, the circle is difficult as a basis for composition because there are no inherent parts to work with in a perfect circle—no horizontal and vertical edges, no corners or gravity. Any definition like up and down or side to side resists interpretation because the eye remains focused on the singularity of circularity as the dominant expression.

So Piero di Cosimo was given this commission and decided on the subject of the Nativity. When we study the painting, we can ask: what is this image about? What does the composition reveal? What did Piero want us to think as we contemplate its iconography?

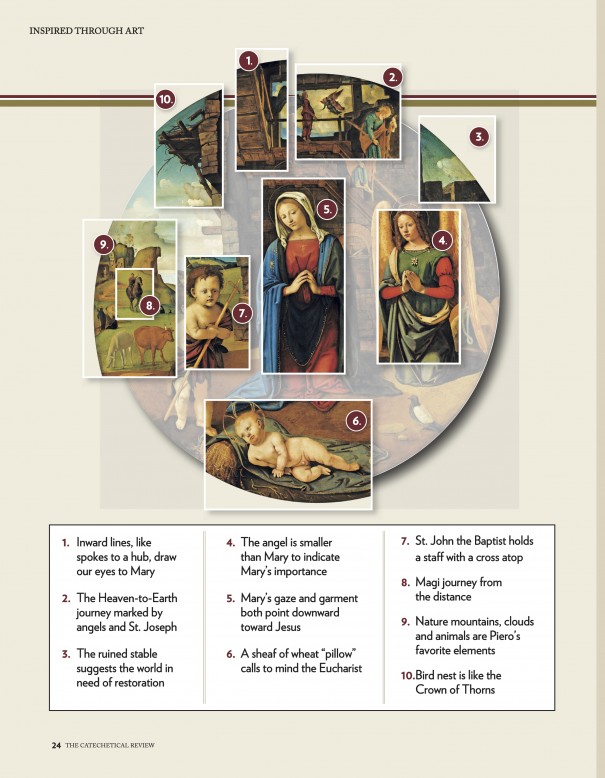

We might begin by confirming that, as much as this painting is about the Nativity of Jesus, it is also a Marian image. Mary is the largest figure and is central in the tondo. This is not to diminish Jesus, who lies at the bottom of the panel. But when we contemplate the journey Mary has made from the Annunciation to Bethlehem with Jesus safe within her womb, we can certainly understand that Mary would be beaming with happiness and a sense of maternity that is cosmic in dimension. She is the human vessel chosen by God to bring the Savior into the world. He is God, and flesh of her flesh, and now the next stage of the Narrative of Salvation can begin.

There are many characters in this painting, so the complete narrative is expansive. We do not read in the Gospels that St. John the Baptist, the cousin of Jesus, was in Bethlehem. It is unlikely that the boy, John, depicted here with a child’s cross on a staff and a prophet’s robe, would have attended this gathering. But there is deep meaningfulness in his presence. As the last of the prophets, John will proclaim “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn 1:29) and “He must increase; I must decrease” (Jn 3:30). The presence of the child John not only connects him as the future prophet but adds a charming element of familial connection.

There are a number of angels present at this scene. Looking through the aperture at the top of the painting is like looking through to heaven; the angels appear to be gathering from a distance—two in the clouds, one greeting them at the landing of the staircase, and one already arrived next to Mary. These steps and stopping points of visual narrative—angels moving from heaven to the Child Jesus—pass through the figure of St. Joseph on the staircase. Remember that while St. Joseph was “in the background” of the Incarnation, he was a very, very busy saint once Jesus became present in our world. Angels communicated instructions again and again: take in Mary as she is with child, go to Egypt to escape Herod, then go to Nazareth to be safe from Herod. Here Joseph is depicted, as in tradition, as an older man. He gingerly descends the rickety staircase that connects the background and the foreground. Piero is certainly including him as a helper and guide in the journey of Jesus and Mary.

Other references to the forward journey of Mary and Jesus are everywhere. The ruin of the stable recalls the broken world in need of restoration. The bird’s nest on the side of the building represents the Crown of Thorns that is in the future. Note also that the little staff/cross St. John carries points directly toward Mary’s face—a foreshadowing of the sorrows that will be borne by the Mother of God. And the sheaf of wheat under the head of Jesus certainly signifies the Eucharist.

While we don’t read in the Gospels of angels or St. John at the stable, we do read in Matthew 2:1–2 of the Magi, the wise men from the East who followed the Star of Bethlehem to find the new King of the Jews. We see the Magi approaching on horseback on the roadway in the distance where a bucolic landscape suggests a Mediterranean Summer more than Winter in Palestine. The Magi’s entry into the scene is literal—a journey from the distance. But there are other journeys and stopping points of contemplation in this scene. Note that linear direction is given to us both by straight lines but also by objects, edges, and shapes. Remember the tondo form: a circle that requires suggestions of movement to keep the eye engaged. The branch supporting the bird’s nest points to the center. The railing of the background staircase is a zig-zag linear map of how to get from above to below; when it reaches the head of the large angel, his downward gaze completes a visual journey from the heavens to Jesus. In fact, almost everywhere in the painting there is some element of direction to move the eye. As still as the moment is in a literal sense, the visual cues are alive with movement and time. Piero wants your mind to move through and contemplate the story of Salvation.

And who is in the center? To whom do these inward lines and edges point? To Mary, of course. In this maternal moment we can see the peace and happiness of Mary as she gazes and directs us to join her in worship of her Son. In Eastern iconography, the form called Hodegetria, or “She Who Shows the Way,” depicts Mary w ith an open-hand gesture toward the child Jesus in her arms. In that type of image we are instructed to do something, just as when Mary said to the wine servers who were to witness the miracle at Cana: “Do whatever he tells you” (Jn 2:5). Even Mary’s clothing directs us to Jesus—notice the downward-pointing “arrows” above her hands, in the center drape of her blue cloak and at the front of her red dress on the ground. All these visual cues point us to Jesus. In this image by Piero di Cosimo, our eyes are first drawn to Mary. In that way we might especially know The Way: through Mary by following her to her Child, our Savior the newborn King.

Linus Meldrum is Associate Professor of Fine Arts at Franciscan University, where he teaches the core curriculum course, Visual Arts and the Catholic Imagination, as well as Studio Art.

This article originally appeared on pages 21-24 of the printed edition.

Open access of painting courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.